PSI is pleased to launch today a first report and overview of climate security practices. Climate security research has evolved tremendously over the past 20 years in the direction of how to address security risks related to climate change. Action on the ground is still limited but holds a lot of potential. Therefore, interest is growing in the development, diplomacy and defence sectors to engage in this space. The climate security practices project from the Planetary Security Initiative seeks to open up a new and vital area of analysis in the climate security community: When it comes to action, what works, and what doesn’t?

Although it is still too early to answer this question, it is possible to collect climate security practices and draw lessons from their implementation. With the climate security link having become more evident in many countries and regions of the world it is imperative to scale up efforts to address the climate security nexus and to learn from these efforts. The Planetary Security Initiative aims to inspire learning on how we can combat this complex risk, or at least alleviate security risks related to climate change, and consider it a new entry point for conflict prevention and peacebuilding efforts.

Climate security practices are defined as: “tangible actions implemented by a (local or central) government, organisation, community, private actor or individual to help prevent, reduce, mitigate or adapt (to) security risks and threats related to impacts of climate change and related environmental degradation, as well as subsequent policies.” (Climate Security Practices report, 2021).

The first report, jointly released with the website launch, draws lessons from and reflects on 8 climate security practices that enhance peace and stability. Many peace-building interventions try to address a wide range of conflict drivers, which include the various manifestations of climate stress such as pressure on natural resources, livelihoods and human security. These can arise from desertification, lack of access to water and unequal natural resource distribution. Examples of these interventions include tree-planting projects, the inclusion of natural resource distribution measures in peace treaties and provision of renewables in refugee camps and military missions. The projects will cover a wide range of practices ranging from human security to hard security-focused practices implemented by actors in the development, diplomacy and defence sectors.

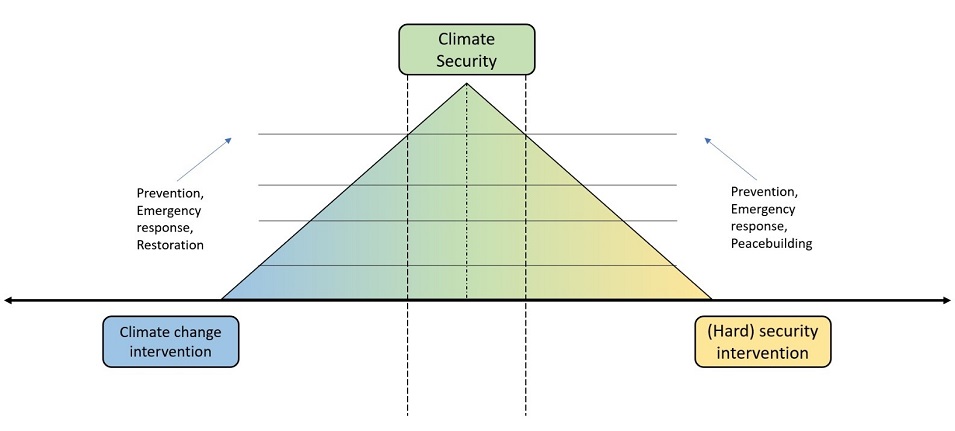

To better conceptualise how climate security practices are operationalised, PSI has developed the climate security triangle model. It helps to map the complex interrelationships between climate security interventions and their intertwining goals; these tend to stem from pure security and climate interventions but ranges to programmes that explicitly address both threats. The report distinguishes between micro-level and macro-level initiatives for further conceptual clarity. Micro-level initiatives are usually designed with a specific local context in mind. These often include the beneficiaries of the project in the design and implementation stages. They typically integrate local dynamics of livelihood security, food security and their impact on overall security by empowering locals to adapt to climate change. The short time scale on many of these projects is the main drawback, but they are less difficult to implement and can be scaled up more easily if successful.

By contrast, macro-level initiatives like “greening the Sahel” try to enhance climate security on a large scale and are usually implemented by external actors. These processes often have nebulous goals, and their impact can be difficult to measure. However, they can have a significant long term impact by creating larger scale positive run on effects in both climate adaptation and stability.

The recommendations of the report follow three main lines:

Firstly, because efforts to undertake action in this field are still developing, all actors working within it should more systemically report on relevant aspects of their projects to enhance our understanding of the field. Likewise, attempts should be made across organisations to learn from others working in the field

Secondly, when working in regions affected by climate change, military actors must shift their focus onto the climate-security nexus as one that often underpins other causes of insecurity like governance failure, inequality and marginalisation. In order to work within this paradigm, military actors could work more extensively with civilian actors on environmental peacebuilding and climate adaptation and mitigation projects.

Lastly, because the results of work in the climate-security nexus are not easily measured quantitatively or in a results-based manner, it is imperative for policymakers to focus on the bigger picture. This often means undertaking projects which have a higher risk of failure as a part of the learning process. However, this should go hand in hand with development in monitoring and evaluation methodologies to ensure that in the long-term climate-security interventions can be accurately monitored.

Climate-security practices hold a lot of potential and will grow in importance. Now it is necessary for the community of practice in the field to increase our understanding and mutual learning about the impact of these practices.

Read the report HERE. See PSI climate - security practices map & overview HERE