Journal article published by The Extractive Industries and Society - ScienceDirect, March 2025.

Militaries are among the world’s most carbon-intensive institutions, yet their emissions remain largely invisible in international climate negotiations. Estimates suggest global militaries account for up to 5.5% of total greenhouse gas emissions, but these figures are rarely officially reported due to national security exemptions. This knowledge gap severely limits the world’s ability to develop meaningful climate targets. This article proposes a practical, bottom-up solution of equipping researchers and civil society actors with tools to calculate military emissions from the ground up.

Concrete Evidence: T-Walls in Iraq as a Case Study

The article does an empirical deep dive into the U.S. military’s extensive use of concrete T-walls during the Second Iraq War (2003–2008). These towering barriers, initially deployed to shield troops and civilians from insurgent attacks, rapidly became ubiquitous across Baghdad. Their function extended beyond protection—they transformed urban landscapes, divided communities, and left a long-term environmental legacy.

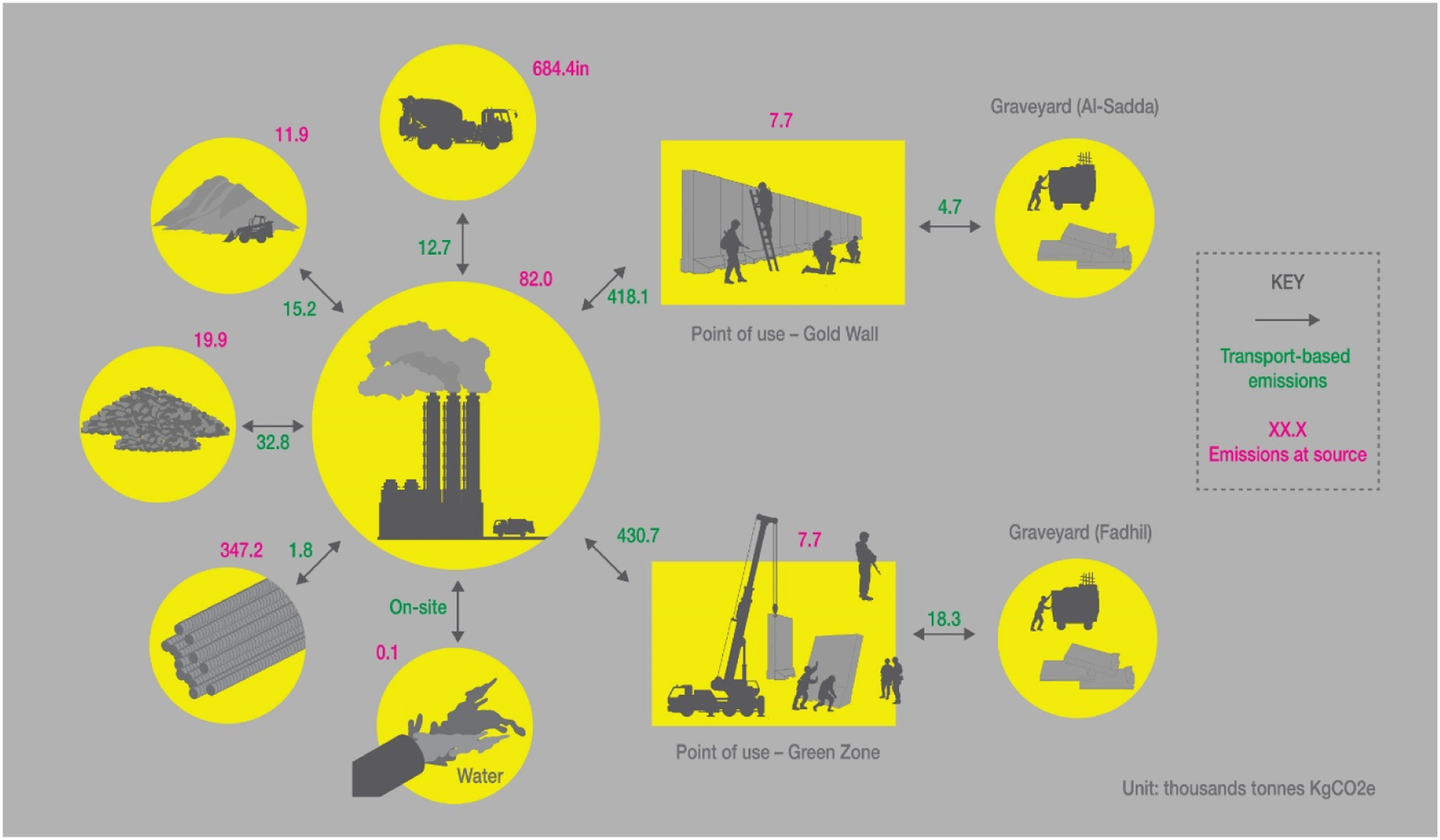

The study reveals the staggering carbon impact of this military concrete use. Each T-wall emits around 1,600 kg of CO₂ equivalent, with the total deployment estimated to produce 54,800 tonnes CO₂. This is comparable to emissions from nearly 13,000 cars driven for a year. Yet these numbers represent only a fragment of the U.S. military’s overall wartime emissions footprint.

A Framework to Navigate the “Fog of War”:

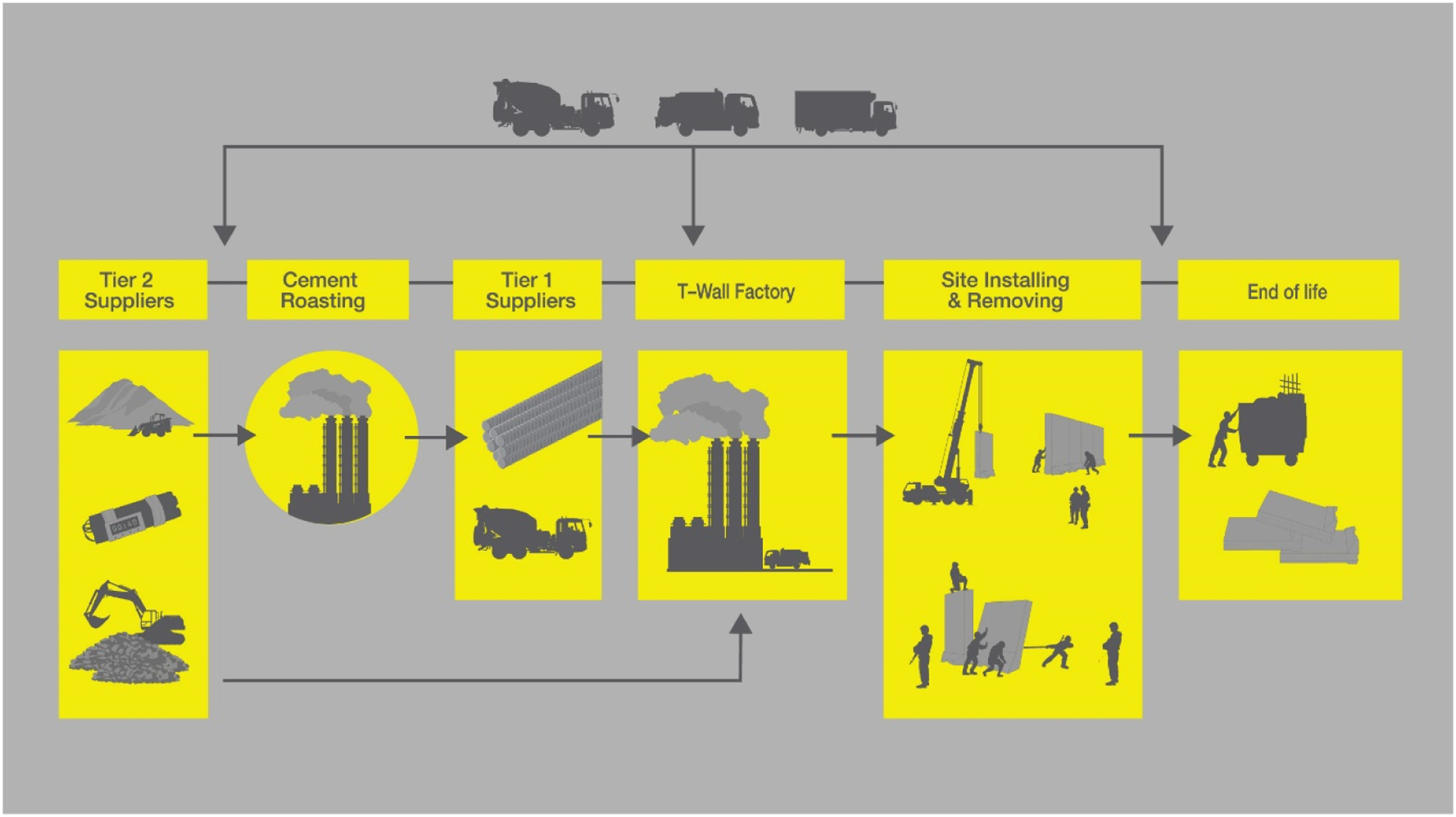

Faced with opaque supply chains and withheld data, the article discusses a robust Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) framework, breaking the T-wall supply chain into five critical stages:

- Extraction of raw materials: Aggregates such as sand and stones were sourced from riverbeds, often damaging aquatic ecosystems and altering river flows.

- Concrete production: Cement, the most carbon-intensive ingredient, was manufactured in deregulated, war-accelerated zones with minimal environmental oversight.

- Transportation: Walls were hauled across vast distances, from Northern Iraq to Baghdad, using heavy-duty trucks, further adding to the carbon burden.

- Emplacement and use: Heavy machinery deployed T-walls throughout Baghdad. Though modular, they were often moved multiple times, increasing emissions.

- End of life: Many walls now languish in “concrete graveyards,” while others are dumped or slowly disintegrate in urban lots, extending their environmental impacts far beyond their initial use.

From Local Extraction to Global Implications:

Beyond emissions, the article highlight how military construction disrupts local ecologies and economies. In Iraq’s Bazian Valley, limestone blasting for cement production flattened hillsides and intensified dust and air pollution. Farmers reported shrinking water access, while local communities bore the brunt of environmental degradation without receiving economic benefits, as labour was often outsourced to cheaper foreign workers.

These lived realities underscore a critical point that climate justice and demilitarization are deeply intertwined. For affected communities, the impacts of militarized concrete go far beyond carbon—they reshape livelihoods, environments, and political agency.

A Call for Accountability and Action:

The article argue that without accurate, independent calculations of military emissions, global decarbonization efforts remain fundamentally incomplete. Their framework offers a replicable model for others working in conflict-affected or politically sensitive contexts, showing that even the most complex and secretive supply chains can be unpacked.

In a world grappling with escalating climate emergencies and geopolitical tensions, recognizing and accounting for the environmental costs of war is not optional—it’s urgent. The study closes with a vital reminder that a decarbonized war is still a destructive war. But by revealing its true cost, perhaps future conflicts can be avoided altogether.

This text is based on extracts from a journal article written by Reuben Larbi , Benjamin Neimark, Kirsti Ashworth and Kali Rubaii, March 2025. The complete article can be found here.

See below for our coverage on similar topics:

- Climate damage caused by Russian War in Ukraine in three years: The key numbers

- Armed Conflict Causes Long-Lasting Environmental Harms

- Irish Defence Forces Review 2024: Climate Change, Security and Defence