A Brief published by the ECDPM, November 2025.

The EU’s Global Gateway strategy is expanding infrastructure investments, especially in renewable energy and green transition sectors, at a time when many critical raw materials and strategic energy opportunities lie in fragile and conflict-affected contexts (FCACs). This briefing argues that while climate sensitivity is increasingly mainstreamed, conflict sensitivity remains insufficient, leaving infrastructure projects at risk of exacerbating tensions. It calls for integrated, participatory and peace-positive approaches to ensure EU investments promote resilience, inclusivity and long-term stability.

Why climate and conflict sensitive infrastructure matters?

Infrastructure directly shapes access to resources, services and opportunities. In FCACs, where political instability, environmental stress and resource competition coexist, infrastructure can either mitigate tensions or reinforce them. Climate-blind planning leaves projects vulnerable to shocks such as floods or droughts. Conflict-blind planning can disrupt pastoral routes, marginalise communities or deepen grievances.

Examples such as Niger’s “peace infrastructures,” involving community-led agreements around shared assets like boreholes and feed banks, show how inclusive processes strengthen cohesion. However, conventional planning often ignores fragility risks, conflict analysis tools remain inconsistently applied, climate and peace goals are addressed in isolation and governance gaps weaken local ownership.

The EU’s evolving approach to infrastructure and water resilience:

Global Gateway marks a shift from fragmented development aid toward a coordinated, geostrategic model for infrastructure investment. Its six principles and 360-degree approach offer opportunities to integrate climate and conflict sensitivity, but implementation remains uneven. The “green and clean” principle embeds climate commitments, including the “do no significant harm” requirement, while conflict risks remain under-addressed. The “security-focused” principle prioritises infrastructure safety rather than underlying conflict dynamics.

Water is emerging as a central strategic concern. The 2025 European Water Resilience Strategy links water scarcity to conflict and displacement and allocates substantial resources for transboundary basin governance. Still, it lacks clarity on how conflict sensitivity will guide water infrastructure investment. The EU’s support for the Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystem nexus further underscores the need for integrated governance.

The opportunities and risks of the green energy transition:

EU policy shifts from the European Green Deal to the Clean Industrial Deal and Critical Raw Materials Act reinforce the strategic importance of green energy and CRM security. Yet conflict sensitivity and local governance risks remain insufficiently addressed. Examples from Kenya’s Turkana Wind Farm and Morocco’s solar and wind installations in Western Sahara show how weak consultation, land disputes and unequal benefit sharing can deepen tensions.

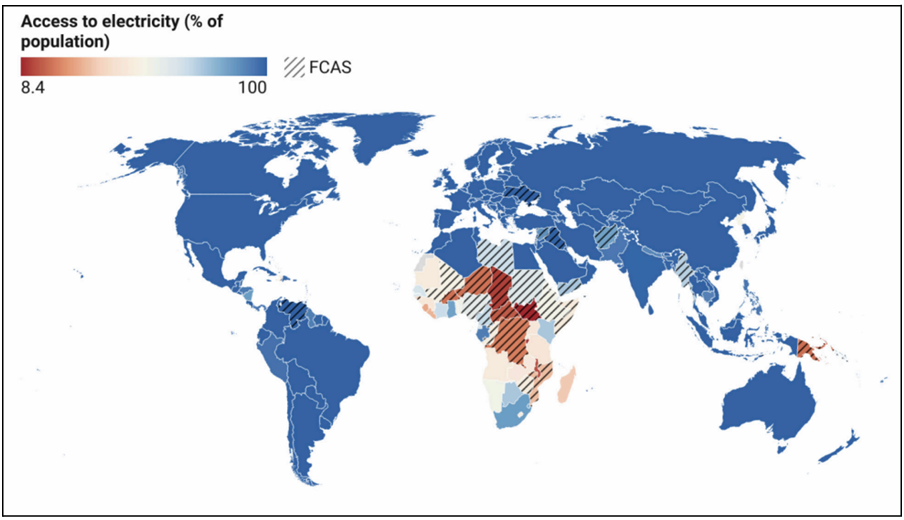

Despite these risks, decentralised renewable solutions hold transformative potential in FCACs where energy access remains extremely low. Falling solar costs create opportunities for scaled investment, but these require deep local engagement and conflict-aware planning.

Lessons from practice: Peace-positive and Nature-based approaches

The briefing highlights good practices where organisations apply climate and conflict sensitive approaches to water and energy infrastructure. Multi-use water points with shared access rules, co-designed irrigation systems and women-led cooperatives in Mali demonstrate how local ownership strengthens cohesion. Nature-based solutions also show promise for reducing environmental and conflict risks, though they remain underfunded.

Referring to a Clingendael policy brief, the note underscores that peace-oriented investments in renewable energy can generate economic and social opportunities and improve energy security, but even decentralised systems in fragile settings remain exposed to geopolitical pressures. This adds to the need for inclusive, transparent management to prevent exacerbating tensions and ensure communities benefit from green transition projects.

Implications of the next EU multiannual financial framework:

The proposed Global Europe Instrument (2028-2034) consolidates external financing and increases flexibility but risks diluting climate commitments and weakening conflict analysis screenings. A stronger alignment with competitiveness priorities may shift resources toward geoeconomic goals rather than peace and resilience needs.

Key recommendations of the brief include:

- Integrate gender, climate and conflict-risk assessments into all Global Gateway and GEI programming, updated as contexts evolve.

- Establish credible alternatives to climate targets and link project selection to resilience indicators.

- Prioritise decentralised water and energy solutions supported by peace-enhancing mechanisms and nexus-based planning.

- Strengthen inclusive governance, participatory planning, land and water dispute resolution, and meaningful engagement with civil society.

- Align EU, member state and DFI investments around shared accountability frameworks with peace-positive indicators and transparent monitoring.

This text is based on extracts from a brief written by Sara Gianesello and Sophie Desmidt, November 2025. To read the complete piece, follow the link here.

Photo credit UNAMID on Flickr

See below for our coverage on similar topics: