Based on the chapter 'Climate Change, Environmental Peacebuilding, and Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism' from the book Resillience, Peacebuilding, and Preventing Violent Extremism, published July 2025.

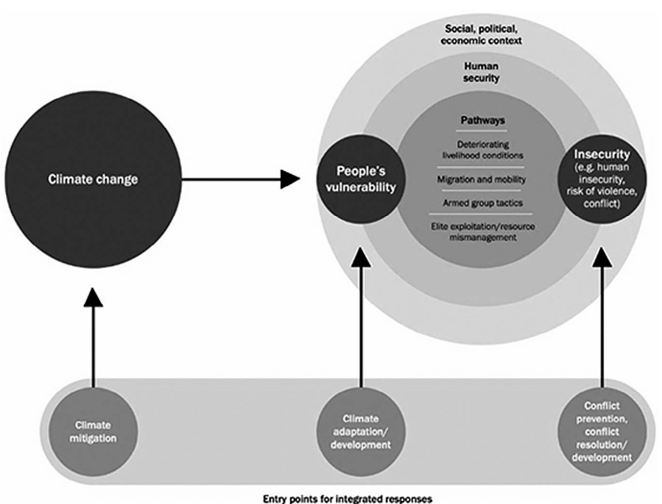

Climate change is no longer a distant threat but a present and intensifying driver of insecurity, especially in conflict-prone and fragile contexts. This chapter explores the intricate links between climate change, environmental degradation, conflict, and violent extremism, advancing the argument that environmental peacebuilding offers a promising avenue to enhance societal resilience and sustain peace.

Intersecting risks and pathways:

Climate change exacerbates vulnerabilities by undermining livelihoods, especially in communities dependent on rain-fed agriculture. These pressures increase competition over resources such as land and water, intensifying existing socio-political grievances. Violent extremist groups often exploit such grievances, offering alternative governance, justice, or livelihood options, particularly where state presence is weak. However, the relationship is not linear or deterministic. Local agency, context, timing, and adaptive capacity all mediate how climate stress translates into conflict or cooperation.

Drawing from the IPCC’s findings and wider literature, the authors emphasize that climate change and conflict interact in compounding and cascading ways. Key risk dynamics include:

- Compound risks: multiple stressors mutually reinforce one another.

- Cascading risks: one disruption triggers sequential crises.

- Emergent risks: new risks arise from unrelated but converging trends.

- Systemic risks: cumulative threats endanger entire systems.

- Existential risks: impacts so severe they threaten societal survival.

These risks illustrate why the effects of climate change cannot be addressed through conventional, siloed security responses.

Exploitation by extremist groups:

Violent extremist organisations adapt their strategies in response to climate-induced disruption. They recruit from populations rendered economically desperate, provide services in neglected regions, and exploit extreme weather events for tactical gains. For instance, groups like Al Shabaab and Jamaat-ud-Dawa have positioned themselves as alternative relief providers during droughts and floods, while in Somalia, flooding has been used strategically to isolate communities or hinder government mobility. Such dynamics deepen fragility and weaken public trust in state institutions.

The role of environmental peacebuilding:

Environmental peacebuilding offers a compelling alternative by addressing the root causes of vulnerability. It seeks to strengthen local institutions, foster cooperation over shared resources, and build adaptive capacity. It operates on three core mechanisms:

- Contact hypothesis: intergroup cooperation reduces hostility.

- Norm diffusion: transnational environmental standards empower communities.

- State service provision: equitable environmental governance builds legitimacy.

Examples like micro-hydropower projects in Nepal demonstrate how climate adaptation efforts can also strengthen social cohesion and hybrid local-national governance systems. However, poorly designed interventions can backfire, as shown by the Salma Dam in Afghanistan, which increased local water scarcity and tensions.

Integrating climate security into Preventing/Countering Violent Extremism (P/CVE) strategies:

The authors propose five pathways for integrating climate considerations into efforts to prevent and counter violent extremism:

- Situational analysis must assess local vulnerabilities, with attention to gender and social stratification.

- Cross-sectoral coordination is essential between peacebuilders and environmental actors.

- Institutional learning should enhance climate-security expertise and early warning systems.

- Community engagement ensures people-centred design and trust-building.

- Operational transformation includes greening peacekeeping missions and supporting local renewable energy transitions with conflict sensitivity.

Resilience and peacebuilding-informed strategies are more effective than reactive, security-heavy approaches. Strengthening communities’ adaptive capacities, social cohesion, and local governance enhances their ability to cope with climate shocks and resist extremist influence. The challenge is not merely to respond to climate-driven risks but to proactively shape conditions that enable peaceful, cooperative responses. Climate change must thus be seen as a defining factor in twenty-first-century peace and security policy.

This text is based on extracts from a chapter written by Florian Krampe and Cedric de Coning, July 2025. To read the complete chapter, follow the link here.

See below for our coverage on similar topics:

- Climate, Peace and Security Fact Sheet: Haiti

- The Missing Climate Factor: Why European Military Interventions in Niger Have Failed

- Destabilization From ‘Within’: A “Termite Theory” of Climate’s Pathway to Violence