In November 2021 at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), world leaders raised promising perspectives and outcomes on how to move on with accelerating the world’s response to climate change. Yet, one topic that has been overlooked is the impact of climate change on security. But how is climate change threatening our security?

Climate security – also known as ‘climate-related security risks’ – is a field of research and policy development which focuses on the nexus between climate change and (in)security. It looks at how climate change contributes to or exacerbates instability. In many parts of the world climate-related pressures, such as extreme weather events, rising sea levels or water scarcity threaten livelihoods and increase competition over food, water and land. If not appropriately addressed, the competition over such progressively scarce resources can turn into major security risks. Climate change can also trigger migration towards urban and less climate-stressed regions and increase socio-economic tensions among the population. When it is combined with other political or socio-economic pressures, its impacts can exacerbate existing drivers of insecurity and conflicts. Bearing this in mind, governments, international and local organisations across the world have realized the importance of designing context-specific practices to address security threats induced by climate change.

Climate Security Practices

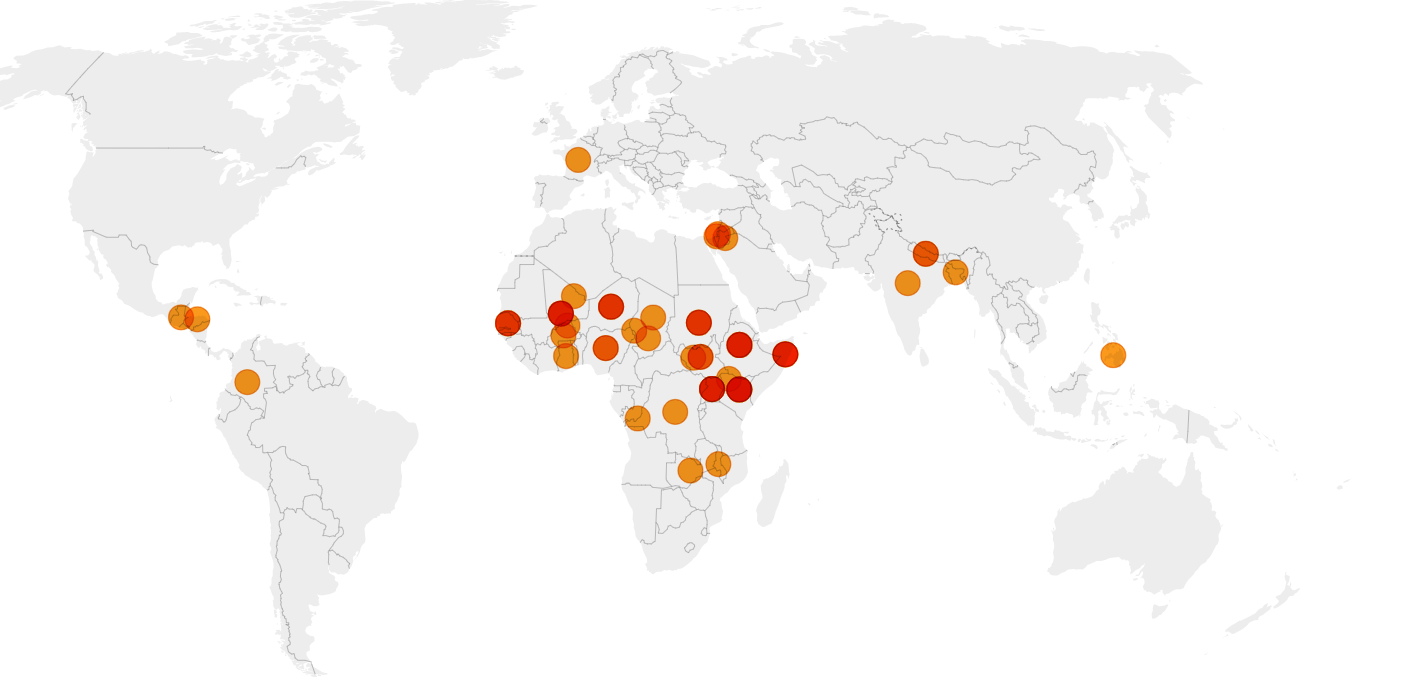

In many parts of the world, vulnerability to the impacts of climate change correlates with high levels of insecurity, which undermines the ability to respond or adapt to these impacts. With an increasing frequency of high temperatures, droughts and other climate pressures, a new line of climate action has emerged to address climate-related security risks. A first overview of climate security practices was published by the Planetary Security Initiative (PSI) in early 2021. Climate security practices are a broad set of actions that prevent, reduce, mitigate or adapt to climate change-related risks. For example, a climate security practice can facilitate mediation among conflicting groups, initiate new land restoration or disaster response or provide renewable energy in refugee camps.

Climate security practices have come to light in different regions of the world, especially in those mostly hit by climate change. Here, we briefly elaborate upon four examples of ongoing climate security practices from the Middle East, South-East Asia, South America and East Africa.

Overview of climate security practices, Planetary Security Initiative (PSI) (2021)

Green-blue deal for the Middle East

Extreme water scarcity in the Middle East is not new to the region but the impact of climate change has amplified the problem. This exacerbates existing tensions over the Jordan river between the riparian countries Israel, Palestine and Jordan. A climate security practice incorporates climate-related measures as a means of conflict resolution and peacebuilding – with benefits for all parties. The initiative ‘Green Blue Deal for the Middle East’ aims to turn water scarcity from a threat multiplier to a multiplier of trust-building opportunities by emphasizing the importance of water. The deal envisages closer cooperation among Israel, Palestine and Jordan over natural water reallocation, water management and renewable energy generation. It promotes increased interdependence among the parties as an important stabilising factor in a conflict-mired region. This practice can enhance peace dialogues in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict while increasing water security in the region.

Kauswagan from arms to farms project

Since the late 1960s in the Philippines, the Moro Muslims have been suffering from political tensions due to poverty and social exclusion which escalated into the violent Moro conflict. Armed insurgent groups, including the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), have fought to establish an independent state in the Southern region of Mindanao. A study shows that the variation in rainfall patterns –which is exacerbated by climate change – negatively impacts agricultural production. As a consequence, poor harvests increase recruitment opportunities for the MILF. Since 2010, the municipality of Kauswagan has started “From Arms to Farms”, through which former MILF combatants learn farming as a way to reintegrate into society and thus improve food security, a root cause of the Moro conflict. This climate security practice has proven effective in reducing poverty and contributing to conditions for peace.

Colombian peace process

The Amazon, covering half of Colombia’s territory, is the world’s largest rainforest and essential in fighting climate change because of the large amount of CO2 it absorbs. Yet this lush forest and its biodiversity is threatened by several climate pressures exacerbated by illegal activities, such as large-scale logging, cultivation of coca, and species trafficking. In turn, its degradation threatens the social and economic stability of the local populations, who are counting on the forest’s natural resources for their livelihood. In 2016, a peace agreement was signed between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The peace process supports strategies for rural economic development, land restoration, and reintegration of former fighters. The Colombian security sector has also initiated a campaign on illegally grown crops in the forest – the third-largest source of deforestation in the country. The campaign has been successful in combating coca cultivation but has not yet eliminated the problem of deforestation for which the Colombian security forces have set a goal of growing 180 million new trees. The peace agreement, in this regard, intends to protect the rainforest and implement rural development schemes to ensure stability.

Cross border cooperation in the Greater Karamoja Cluster

The Greater Karamoja Cluster in East Africa encompasses areas of Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan and Uganda. Here, climate change aggravates existing drivers of insecurity and is eventually one of the sources of the emergence of violent conflicts, such as between the communities of the Turkana, Pokot and Karamoja. In the region, pastoralism is the predominant livelihood model. Intensified droughts and desertification contribute to escalate intra-community conflict over scarce resources and land access. To reduce this vulnerability, international, national and local organisations, such as Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), have implemented several measures to increase cross-border community coordination over livestock mobility and natural resource management. Thanks to a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed between Kenya and Uganda in 2013, Turkana pastoralists from Kenya could move into Uganda to graze their cattle during the 2017 drought without entering into conflict with the local Karamojong people. This coordination and sharing of resources have proven successful in reducing the vulnerability of the communities to drought as well as promoting peaceful coexistence of communities.

Climate-security practices – a peace engine?

The above examples illustrate what can be done to address the climate-security nexus. Insights into climate-related risks such as deforestation and droughts can and should more systematically be integrated in broader peacebuilding efforts. as in the cases of the Green Blue Deal or the Colombian Peace Process. Likewise, practices can create conditions for peace by addressing the root causes of conflict, as From Arms to Farms which also aims at increasing food security or MoU between Kenya and Uganda which provides a flexible response to resource scarcity. Assessing the effectiveness of climate security practices is harder in comparison to other peacebuilding efforts. These practices do not take place in isolation and it is always difficult to prove the prevention of conflict or contribution to stability. However, this field arguably holds a lot of potential for peacebuilding, peacekeeping and mediation and, hence, should be increasingly taken into account by practitioners in the field of conflict and security.

By Maha Yassin and Giulia Cretti

This article was first published (with adaptation) in Release Peace on 5 December 2021.