A devastating uptick in violence in Mopti has drawn fresh attention to ethnic divisions and radicalisation. However the role of natural resource pressures as a root cause of conflict and point of departure for solutions continues to be overlooked. Here we set out an ambitious case of interventions – based on extensive research from the PSI community of practice – which both development and security actors can utilise to stem the spread of violence and establish the foundations for peace.

On Saturday 23rd March, over 160 civilians, mostly semi-nomadic Fulani herders, were massacred in the villages of Ogossagou and Welingara in the Mopti region of central Mali. To explain the attack, much of the international coverage looked to ethnic divisions and radicalisation, namely between the Fulani and the settled Dogon group of farmers, the alleged attackers. The Fulani have been accused in the past of threatening sedentary livelihoods and aiding jihadist groups in the region.

However, there are deeper and often overlooked root causes that long predate this escalation, factors which now serve to lengthen and exacerbate the crisis. As documented in a 2017 briefing by the Planetary Security Initiative, population growth and climate change have played a fundamental contributing role to Mali’s fertile grounds for conflict. As one academic observed, “As demography has increased, the bush has diminished.”

The path from peace to violence becomes clearer through this holistic lens. Ethnic groups of farmers and pastoralists like the Dogon and Fulani have long competed over access to natural resources, principally land and water. But whereas in the past these communities were able to coexist, with conflicts managed by customs and local chiefs, the stress and risks to livelihoods emanating from climate change and population growth has increased the inherent tension of negotiations.

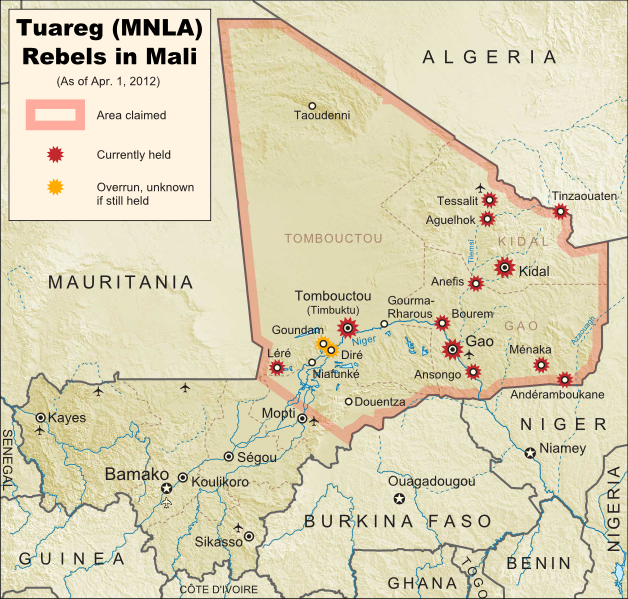

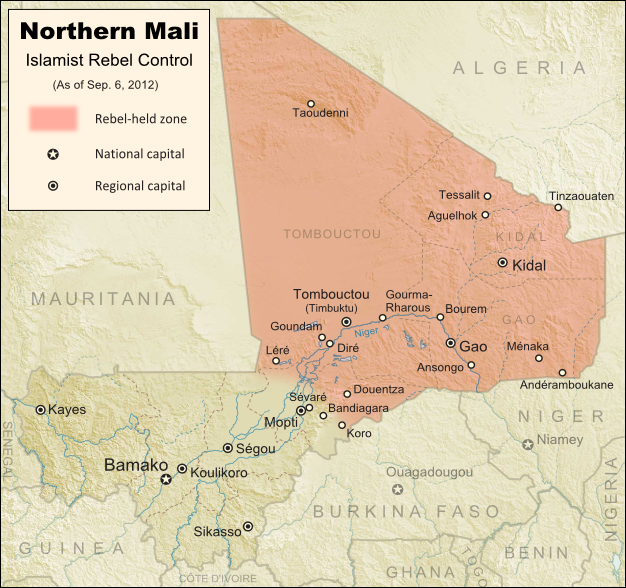

Mali only really came under the international spotlight in 2012, when an armed separatist rebellion among the Tuareg ethnic group in the north occurred alongside a proliferation of Islamist extremist groups, an inflow of heavy weapons from Libya, and a severe drought. The already politically and economically marginalised northern region suffered intensely in the following years, as did central Mali, as strife and insecurity spread. Violence surged, the rule of law receded and extremist Islamist groups were able to fill the vacuum.

An additional problem are large investors from Bamako, who often have close links to the policy elites. They have bought lands and changed agricultural practice, reducing available land for smallholders and herders, and for local leaders it proves difficult to overrule them. Thus, instability in regional geopolitics, exploitation by armed ethnic groups and poor recourse to state law enforcement have together caused tensions to spill over. These conflicts have increasingly borne devastating consequences, with an estimated 202 civilian deaths in 2018 and over 60 in January 2019 alone.

But forgetting about what is at the root of this current violence – competition for the increasingly scarce natural resources of land and water – leaves current interventions incapable of helping to deliver any sustainable peace in Mopti. Though both the EU and the UN Security Council have acknowledged climate change as one of the root causes of conflict across the Sahel region, Secretary-General António Guterres was one of few participants in a Security Council debate on 29 March to recognise it, as well as communal tensions over land and water.

"We often look at arms and armed actors, and maybe at underdevelopment, but now we see that climate change is leading to conflicts among communities and this is a different kind of violence." Peter Maurer, President of the International Committee of the Red Cross, (BBC)

MINUSMA has had climate change a conflict risk factor enshrined in its mandate since July 2018, but it is currently waiting for another extension of this mandate. Some states such as the US are pushing for a significant adaptation, arguing MINUSMA is “operating in an environment far outside the bounds of traditional peacekeeping”. It is unclear currently what MINUSMA activity is ongoing, and if in these efforts the natural resource angle is used as a point of departure.

Unfortunately the potential for inertia on natural resource management is now high, with development and climate adaptation projects currently at risk in light of the deteriorating security situation. At the same time security actors tend not to go in before a full-blown conflict erupts. But difficult as it may be in the face of a fluid and deteriorating situation on the ground, a number of opportunities can be identified for peacekeeping missions and development agencies alike.

- Conflict prevention interventions, for example mediation between pastoralists and sedentary farmers, need to include resource dialogue and agreement. This means going beyond the Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) process that was installed by the peace agreement of 2015. As was argued at the time, the DDR focus may deliver a basis for short-term security, but less so the foundations for a sustainable peace. One overlooked initiative is the strengthening of customary justice systems to create an accessible form of mediation for local resource disputes. Steps to leverage these systems in the short term, and improve and protect them in the long term, would undermine the ability of armed groups such as the Macina Liberation Front to exploit grievances held against what is seen as a corrupt and distant state by marginalised communities in Mopti.

- Interventions that put resource and climate-sensitivity at their core would also provide the foundation for a regionally and nationally coherent strategy. Too often the response to instances of conflict have involved isolating particular local circumstances, specific ethnic divisions and unique contexts of escalating violence and retribution. The targets of these interventions are not oblivious to the shortfalls of such transient interventions, leading to criticism on the ground and a lack of faith in their capacity to legitimately tackle the deep and wide roots of conflict. A national strategy featuring a recognition of and commitment to resource pressures would deliver coherence between the development and military sectors as well as short-term and long-term goals. Exacerbating factors such as the behaviour of big land owners from Bamako would be better incorporated and the need for decentralisation better acknowledged.

- Early warnings of future violence can be improved by developing an evidence base on local and regional natural resource conflict dynamics. While direct evidence of the link between resource pressure and the Ogossagou massacre may not be demonstrable, the conditions that led to it are not isolated – they exist throughout the region and could be identified at their worst in other localities. Targeted interventions can take place where conflict dynamics make the risks of new (or spill-over) violence highest. At the same time, support for innovation and resource efficiency can stem the spread of tension where good relations still exist.

- Development projects, where they continue to operate in central Mali, must account for different livelihoods of pastoralists and farmers and tailor interventions accordingly. This would avoid the exacerbation of existing resource disputes and tensions that the unequal provision of services (for example in education, health and agriculture) can create. Doing so consultatively, and in line with local populations’ priorities, could allow donors to contribute actively to peacebuilding as well as development by fostering greater cooperation in the face of contrasting resource requirements and pressures.

- The focus of projects should increasingly be set on water and land management. Countering the consequences of increasing severe droughts, water resource mismanagement and land (ownership) mismanagement, this approach can provide the basis for new value chains, increase (youth) employment and support the resilience of the population in Mali.

In general the international community recognises in theory the potential to use climate adaptation and natural resource management interventions to peace and stability objectives. However, now a new conflict is emerging in a region where climate change hits hard and divisions between development and security actors prevail. At the same time the securitisation of the Sahel continues, partly in an effort to halt migration to the EU. Despite progress in recent years on practical action to address security risks emanating from climate change and resource pressures, the international community still lacks the tools – and, it seems, the political commitment – to confidently use these insights to inform conflict prevention efforts.

The potential implications of this lack of action are huge, namely a full-blown conflict leading to loss of lives and livelihoods, a new region where terrorist groups take control, a domino effect to other parts of the Sahel region and the potential need for large-scale military intervention. Hence, even in the absence of a complete toolbox on how to act, now is the time to learn by doing, and try to pull off a dialogue on natural resource division in Mali to prevent such a scenario from unfolding in the near future.

Article By: Rob Magowan, Louise van Schaik, Tobias von Lossow and Lars Donkor

Further PSI publications on Mali:

Outcomes of the sessions on spotlight region Mali during the Planetary Security Conference 2019.

This 2017 policy brief by Shreya Mitra documents Mali’s fertile grounds for conflict

This 2017 policy brief by Basak Kalkavan documents outlines possible approaches to strengthen the adaptation in Mali

This 2018 policy brief Anca-Elena Ursu by on the potential of customary justice to reduce conflict over natural resources

The Hague Declaration addresses the interface between climate-related resource scarcity and conflict risk covered in the monitoring of this Declaration,

Video Interview with International Alert Advisor for Climate Change and Security Shreya Mitra

Video overview on Mali’s climate security trap November 2018

Video pop-up documentary on the strength and resilience also represented in Mali

Article on the Sahel related discussions in Davos

Article on the Sahel related discussions at the Munich Security Conference

Photcredit:

UN Photo/Marco Dormino