After several years of low rainfall and a severe drought in 2017-2018, the City of Cape Town municipal government was forced to introduce dramatic measures in order to narrowly avoid the ‘Day Zero’ scenario - almost totally depleted reserves. A new briefing from the Grantham Institute looks at how events arose and how the city managed supply and demand during the crisis, with some important observations on the implications for societal tension and conflict risks of urban water security pressure.

A one-in-300-year low rainfall occurrence over three winters is identified as the main cause of the crisis, though exacerbating factors included high consumption, population growth, a lack of investment in water supply capacity, exports of ‘virtual water’ (embedded in commodities) and an increase in agricultural use.

Average annual temperatures are also noted to have increased 0.14°C per decade over the past 30 years in South Africa, and further increases are expected to have cascading effects leading to an estimated 20% reduction in surface water supply by 2100. The prospect of accelerating climate change – as well as Cape Town’s recent history of rapid urbanisation and large differences in socio-economic statuses – makes the experience an important case study for many urban environments globally.

The full report is here, but a number of direct and potential security implications of the shortage and the response to it can be highlighted:

- Cape Town’s large network of publicly accessible spring water collection points came under dramatically increased pressure, with numbers of visitors at one small spring receiving 7,000 visitors per month – up from 100 before the crisis. In some cases, facilities were not designed to accommodate such volumes, and tensions heightened among collectors and the surrounding community. There were instances of physical fights breaking out, leading to the city supplementing existing private security with police. One spring was closed and water rerouted in aid of traffic and noise management.

- Water Management Devices (WMDs), setting daily limits on properties, were rolled out throughout 2017 first on a voluntary basis (typically in exchange for debt cancellation) and then compulsorily for some high-consumption households. Concerns were raised that WMDs were unfairly targeted towards poor and high-occupancy households, despite their disproportionately low consumption.

- Access to springs, stockpiling bottled water and private access boreholes often involved considerable costs and were available only to a small percentage of households, fuelling resentment and creating tension between different sections of the population. With rich and poor populations commonly divided along racial lines, this had the potential to “further exaggerate and exacerbate historical divisions”.

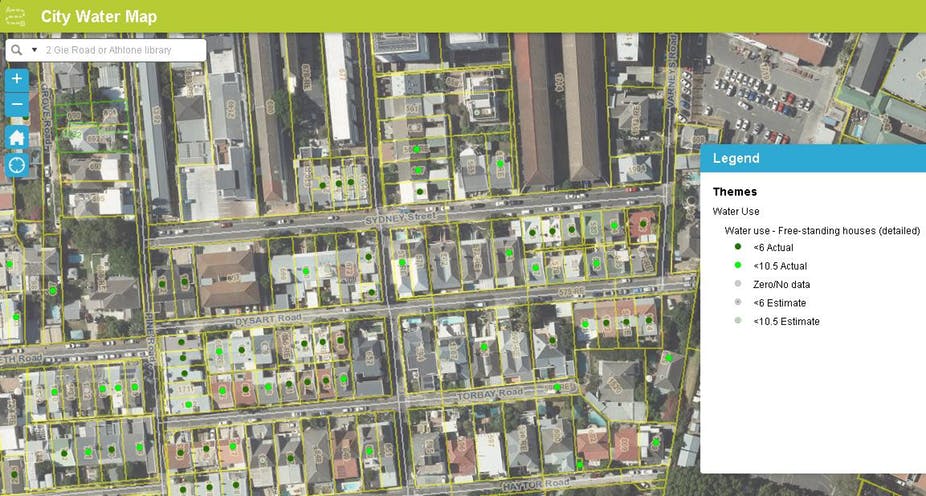

- A ‘Cape Town Water Map’ was developed to indicate exactly which households were achieving reduced consumption targets. This exploited behavioural science research on the effectiveness of public recognition of need and visibility of social norms in incentivising household conservation. Despite positive framing to “paint the town green” however, some felt the measure violated their privacy and was being used as an adversarial tool to shame and put at risk households not marked on the map.

- The municipality faced a dramatic reduction in revenue from water consumption tariffs, leading to a shortfall in the budget and subsequent reduction in other spending programmes.

Highlighted recommendations

- The city’s ‘Disaster Plan’, published in early 2018 and laying out the severe consequences of reaching Day Zero, is credited as the most effective intervention, as it communicated with sufficient clarity and urgency to drive change.

- The Cape Town Water Map, while controversial, also “got the conversation going, and may be a template for other cities to provide a live and accessible resource to help improve usage in times of crisis or otherwise.”

- Sensitivity to different sections of society must be shown to encourage mutual understanding and co-operation, stem tensions between social groups and government and decrease the risk of civil unrest.

Read the full Grantham Institute briefing here, or see the Planetary Security Initiative’s previous research on water, climate and conflict here.