Senior Climate & Security Advisor at the United Nations Mission in South Sudan

In June 2025, PSI spoke with Johnson Nkem, the Climate Security Advisor for the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and the UN Country Team. In his role, Dr. Nkem integrates climate security perspectives into peacebuilding, humanitarian, and development operations in one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable and conflict-affected regions. With a multidisciplinary background, he brings experience from previous roles at UNDP, the UN Economic Commission for Africa, and the IPCC.

In this interview, he shares insights into how climate risks exacerbate insecurity in South Sudan and explains how communities are navigating the growing impacts of climate shocks. He also reflects on cross-border water governance and the role of renewable energy in reducing both vulnerability and violence. Further, he offers his perspectives on balancing climate and defence commitments in global security dialogues.

Could you briefly introduce yourself to our readers and tell us about your current role and responsibilities within the UN system?

My name is Johnson Nkem, and I work as the Climate Security Advisor for both the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and the UN Country Team. My primary responsibility is to integrate climate security perspectives into the mission’s operations, as well as into the broader programming and humanitarian efforts of the UN in South Sudan. My role is to ensure that climate-related security risks are fully considered and embedded within peacebuilding processes.

While the UN Security Council has increasingly acknowledged climate change as a peace and security risk, some states remain hesitant to do so. What more can be done at the international level to strengthen political consensus and action on climate security?

It’s a gradual process. Historically, climate change has been viewed primarily through a development lens, focusing on its economic impacts. The security dimension, however, is now gaining more recognition, although the supporting science and data remain limited, which partly explains the reluctance of some states.

Within the UN Security Council, we’re seeing incremental progress. For instance, the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) became the first peacekeeping mission to have climate security formally included in its mandate, starting with the 2023 resolution. Previously, climate change was only mentioned in preambular paragraphs, but now it appears in the operational part of the mandate, which compels concrete action. This shift enables regular reporting on how climate factors are influencing conflict dynamics on the ground.

In South Sudan, where intercommunal and sub-national conflicts are prevalent, we can clearly trace the influence of climate change on local tensions. As we report these dynamics, Security Council members are increasingly exposed to the real-world implications of climate-related security risks.

Beyond the Security Council, this agenda is also gaining traction within the UNFCCC. For example, the COP27 presidency in Egypt included climate security as a topic of discussion, signalling a broader institutional acceptance. So, while consensus is still evolving, we are seeing climate security emerge through multiple international channels.

What roles do traditional chiefs and local governance structures play in resolving climate-induced conflicts, and how can the UN strengthen their role without trying to replace it?

South Sudan has a layered governance structure, from the national level down to payams, or village units. At this local level, traditional governance plays a central role in managing conflicts and maintaining coexistence, rooted in community trust that formal systems cannot replace.

Traditional chiefs lead cattle migration conferences and local dispute resolution, but their enforcement capacity is limited, especially against armed groups. Strengthening these systems means linking them to formal governance and the rule of law, while respecting their legitimacy.

At the UN, we combine engagement with national institutions and direct support to local structures, which helps depoliticise our work and ensures assistance reaches communities without tribal or party bias. The goal is not replacement but reinforcement. It is to make these systems stronger, more inclusive and better equipped to foster peace.

Transboundary and underground water issues are growing global concerns, and they are only going to get worse. How can countries and communities better cooperate over shared water resources in a climate-stressed world?

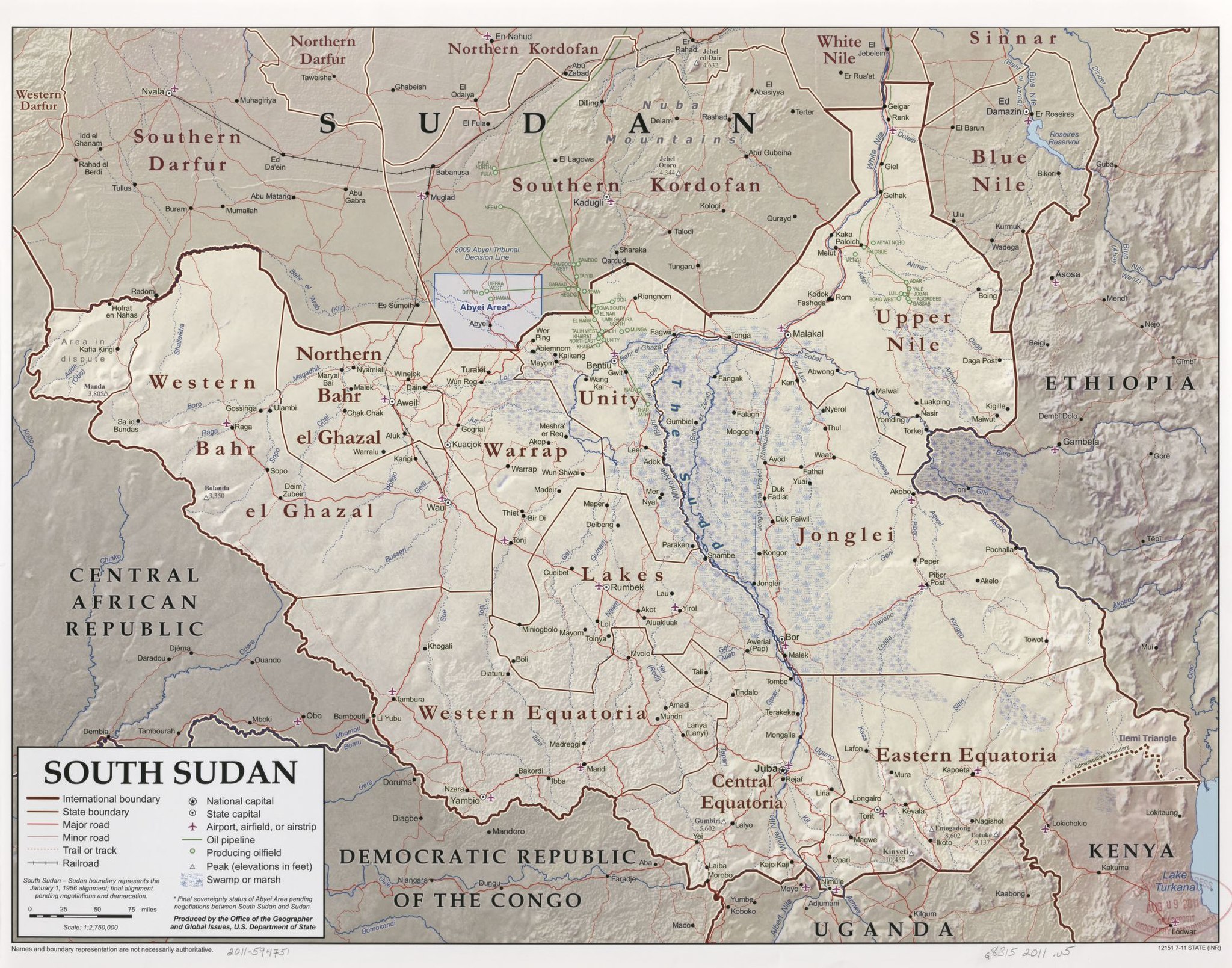

Water is becoming an increasingly critical issue, not only for its cultural and economic importance, but also due to the pressures of climate change. In South Sudan, we’re still dealing primarily with surface water, and the region’s hydrological extremes demand careful management. Transboundary systems like the Nile River Basin are especially vulnerable. The White Nile, which flows through South Sudan, and other shared water bodies such as Lake Victoria and Lake Kyoga, require regional cooperation that accounts for both scarcity and excess.

Climate shocks are making it harder to manage shared water resources, especially where governance structures are weak or absent. Over 60% of Africa lies within transboundary water systems, yet many lack the institutional mechanisms needed for equitable and safe water management.

In South Sudan, two major transboundary water systems are especially relevant. The White Nile, which is distinct from the Blue Nile that flows through Ethiopia, runs directly through the country. Lake Victoria, shared by several nations, has recently shown how excess water can also trigger security risks. In 2024, lake levels reached their highest point in over a century. As a result, Uganda was forced to release over 6400 cubic meters of water per second to protect its dam infrastructure and most of this water flowed downstream to South Sudan. While communicated to us in advance, this posed a severe flood risk.

Effective governance at both regional and local levels is key. It’s not just about sharing water but about sharing climate-related risks. Mechanisms must be in place to coordinate how and when water is released, especially during extreme events. If done haphazardly, downstream communities may not have time to prepare or relocate, exacerbating the humanitarian impact. In South Sudan, the priority is managing these risks collaboratively, rather than merely dividing water resources.

Communities in South Sudan have long relied on traditional strategies to cope with floods and other climate shocks. However, with increasing rainfall and rising water levels, these approaches are under strain. What examples of local adaptation have you seen, and how can they be supported and scaled in ways that strengthen resilience and reduce conflict?

Communities here have always adapted to climate shocks using local knowledge. Traditionally, people moved to higher ground during floods, taking livestock with them, or mobilised collectively to relocate. These low-tech, nature-based practices worked when shocks were less frequent. But today, floods have become almost annual, and with territorial disputes and land fragmentation, mobility is increasingly restricted. Traditional systems alone can no longer cope.

What remains vital is social resilience. Communities still try to rely on established practices, but government involvement is now essential to ensure lawful, safe movement and to safeguard land rights. Without this, relocation risks sparking further disputes. In this sense, traditional coping strategies need to be embedded within formal governance structures, turning spontaneous responses into managed, equitable systems.

We also see shifts in livelihoods. South Sudan is a pastoral society, with over 19 million cattle which is more than its human population. Livestock is central not only economically but also socially and culturally, tied to traditions like marriage and community rituals. Moving away from pastoralism is therefore more than an economic adjustment; it is a societal shift. Yet change is happening. In flood-affected states like Unity, Jonglei, and Warrap, communities are turning to fishing and experimenting with rice cultivation. These are not traditional practices, but they are gaining ground as climate realities reshape options. With support from partners in Bangladesh and Nepal, rice farming is being introduced as a climate-resilient crop. Early results are promising, though there is still a learning curve, both in cultivation and in integrating rice into local diets.

Youth play a particularly important role in driving this change. With South Sudan’s predominantly young population, there is openness to experimenting with new livelihoods when resources and training are available. One promising approach piloted by agencies like FAO is integrated floodplain farming: during high water, people fish; as waters recede, they garden on the saturated banks. This seasonal continuum offers reliable income and helps build resilience. Young people are drawn to these systems because they generate quick returns, support local markets, and create opportunities beyond survival.

Crucially, livelihood adaptation also links to peace and security. When people, especially youth, can earn a living and see a future in new practices, the risk of conflict tied to displacement and resource competition decreases. Economic empowerment strengthens community stability and reduces vulnerability to recruitment into violence.

Despite the global push for clean energy, many communities in South Sudan still rely on traditional biomass like wood fire. Is there a realistic pathway for renewable energy adoption in such contexts, and what could support that transition?

Renewable energy is absolutely critical and not just for climate reasons, but also for development, resilience, and even peace. One of the key opportunities with renewable energy is its potential for decentralized power provision and that’s essential in places like South Sudan.

South Sudan’s geography, especially its high exposure to flooding, fragments the country and renders grid-based infrastructure extremely difficult and expensive to expand. In this context, decentralized renewable systems such as solar mini-grids or standalone systems can rapidly improve energy access, even in the most isolated areas.

Renewable energy is also vital for supporting social services. In many parts of South Sudan, flooding isolates entire communities and disrupts access to essential services like healthcare and education. I’ve seen firsthand how women struggle to reach maternity care, often trekking over three hours under normal conditions and even longer during floods. Clinics and schools are often limited to operating during daylight hours because they lack electricity. Renewable energy can power these facilities, allowing them to stay open longer, serve more people, and function more reliably especially in times of climate-related crisis.

Then there's the household energy dimension, which intersects directly with gender-based violence. During floods, the incidence of conflict-related sexual violence increases particularly as women must walk long distances in insecure areas to collect firewood. Providing improved cookstoves or clean energy alternatives could reduce this exposure. We can’t be certain without testing, but there's strong potential that such interventions would reduce both the frequency and the distance women need to travel for fuel, thereby lowering their risk of violence.

In short, renewable energy in South Sudan has the potential to deliver climate resilience, health and education gains, and even conflict mitigation. But to unlock that potential, significant investment is needed, both in community-based projects and in national-level systems. While grid expansion is important in the long term, it will take substantial time and resources.

You recently spoke at NATO’s Climate Change and Security Centre of Excellence’s first course on Climate security. At a time when the world is contemplating if climate and defence commitments can be managed together, what are your thoughts on it?

One of my key observations is that “climate security” is being interpreted in very different ways, depending on who you speak to. For instance, when I engaged with NATO’s Climate Change and Security Centre of Excellence, as well as at the U.S.-Africa Command (AFRICOM) event in Botswana in 2023, I noticed that much of the conversation in military contexts is framed around defence and offense tactics. Climate change is viewed through a strategic military lens of how can forces defend themselves better or even carry out operations more effectively.

This framing raises a critical question for me on where does peace fit in? If we’re only looking at how to adjust military strategies in response to climate risks without addressing root causes or building peaceful resilience, we risk militarizing the climate crisis rather than resolving it.

That said, I also found it encouraging that there’s growing attention within military institutions to reducing the environmental footprint of operations including carbon emissions, material use, and pollution. That kind of awareness is important, because if the global military footprint remains unchecked, it imposes a heavy environmental and social burden on the very people we're trying to protect.

Overall, I believe there’s value in these dialogues but it's crucial that we don’t lose sight of peace as the central objective of climate security.

How can research institutions such as Clingendael or others better support your work? Are there specific knowledge gaps you’d like to see addressed in the climate, peace, and security field?

Definitely, we need much more research across a wide range of emerging issues. There are so many gaps that it's hard to even know where to begin. The challenge, however, is the setting of both UNMISS and South Sudan itself. While we do collaborate with institutions when they come to conduct studies, the mission’s nature and the local security situation make it difficult to host researchers on a more permanent basis.

That said, we do support visiting researchers in helping them collect data and navigate the context while they are here, before they return to complete their work elsewhere. Personally, given my background, I would have loved to establish longer-term research partnerships. But due to our operational environment and peacekeeping mandate, that’s not always feasible.

Still, there are numerous subject areas in need of empirical research, from local perceptions to operational assessments, all of which can strengthen our understanding and impact. If Clingendael or similar institutions have a particular interest or topic, we’d be more than happy to engage, share relevant ideas, and support your fieldwork whenever possible.

About this series:

In recent years, PSI has conducted interviews with several climate security practitioners. See below for an overview of interviews conducted between 2023 and 2025:

Johanna Lauritsen: In our interview with Johanna Lauritsen, Environmental Coordinator at the Civilian Operations Headquarters of the EEAS, we explored her efforts to mainstream environmental considerations across EU civilian CSDP missions. She highlighted the progress made in integrating sustainability into both internal operations and external tasks, including tackling environmental crime, managing environmental risks, and improving green procurement. Lauritsen also reflected on the importance of staff training, interdepartmental collaboration, and the challenges of working in complex and often unstable environments.

Wilfred Boerrigter: In our interview with Wilfred Boerrigter, Head of Operations at Mandalay Yoma Energy, we explored his work in maintaining solar mini grids in rural Myanmar amid ongoing conflict. He highlighted the severe energy poverty in the country and the role of renewables in enhancing community resilience by improving access to electricity, healthcare, and safety. Boerrigter discussed the challenges of operating in active conflict zones, including site accessibility, neutrality concerns, and infrastructure security. He emphasized that despite these hurdles, renewable energy remains a crucial tool for stability and development in Myanmar.

Christophe Hodder: In our interview with Christophe Hodder, Climate and Environment Advisor for the UN in Somalia, we explored how climate change is exacerbating conflict, displacement, and food insecurity across the Horn of Africa. He described the challenges of balancing short-term humanitarian responses with longer-term climate adaptation, highlighting the importance of nature-based solutions, urban planning, and ecosystem protection. Hodder also reflected on Somalia’s vulnerability to extreme weather events, the need for stronger governance and financing, and the role of international actors in supporting sustainable and conflict-sensitive adaptation strategies.