When African leaders gathered in Addis Ababa for the 2025 Africa Climate Summit, the message was loud and clear: Africa wants to reposition itself towards a leading role in global climate finance shifting from aid to investment. They argued that the continent should not be cast as a passive victim of climate change but as a driver of the next global climate economy. And the way to do that is by shifting from aid to investment.

Theoretically, it makes sense. Traditional aid has failed to deliver the scale of financing needed to confront intensifying climate shocks. Unlocking private capital could, in theory, transform projects like the Great Green Wall from aspirational pledges into tangible lifelines for millions facing drought, floods and desertification. But here lies the tension: private investment often comes with conditions. And in Africa’s most climate-vulnerable regions, those conditions risk increasing vulnerability.

For example, in Kenya’s drylands prolonged droughts have pushed pastoralist communities into ever fiercer competition over grazing lands and water. What were once seasonal disputes have escalated into cycles of violence, often exploited by armed groups. As the case study shows, climate change doesn’t act in isolation, it deepens existing vulnerabilities. It weakens the governance and creates livelihood insecurity, turning scarcity into a trigger for instability. This threat multiplier effect is exactly why the Africa Climate Summit made climate security a central focus.

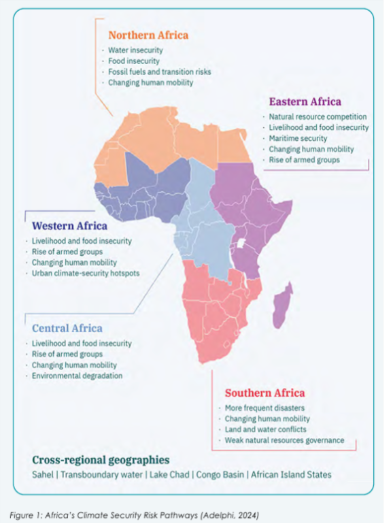

The Climate Security Risk Pathways published prior to the summit maps out how climate impacts interact with existing vulnerabilities: A complex and multi-directional process where climate impacts intersect with pre-existing vulnerabilities to produce security risks (see Figure 1). These risks already happen within volatile contexts where competition over scarce resources fuels insecurity. Add investors demanding guarantees, higher returns or political leverage, and climate finance could become a double-edged sword.

Take adaptation projects, climate-smart agriculture, early warning systems, or resilient infrastructure. These are precisely the initiatives that reduce conflict risks and strengthen communities. Yet for investors, they often look unprofitable - too local, too risky, too slow to generate returns. That gap leaves the most fragile regions exposed, creating a negative outcome where finance flows toward safer projects.

This isn’t just an economic imbalance; it’s a security one.

The summit’s call to reform global finance systems from donor-driven aid to targeted investment is both urgent and valid. But unless governance structures and safeguards keep pace, the shift could lead to more vulnerability. Without stronger protection, the promise of private finance risks entrenching precisely the vulnerabilities it aims to solve. Furthermore, a persistent challenge remains the scarcity of private climate finance. A recent OECD report on "Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries" shows that public finance constitutes nearly 80% of the total, with private finance mobilized by public efforts making up a much smaller portion. According to a policy brief from the research organization SouthSouthNorth, this disparity is due to several factors, including policy and regulatory barriers, a high-risk perception, lack of bankable projects, capacity constraints, and limited access to finance.

This is why the climate–peace–security nexus, highlighted so prominently in Addis, matters. It’s not just about avoiding conflict triggered by drought or displacement. It’s about recognising how financial flows themselves can shape stability. Investment that ignores conflict sensitivity, or sidelines community ownership, is not just risky but also destabilising.

Yet there are also signs of how this shift can succeed. The Great Green Wall Initiative (GGWI) is one of Africa’s most ambitious efforts to link land restoration, sustainable resource management and climate security across the Sahel. Long dismissed as a symbolic tree-planting exercise, the initiative has entered a new chapter. Its 2024–2034 strategy broadens the vision toward integrated natural resource management, aligning with the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and the Sustainable Development Goals.

The challenge is no longer ideas but execution. More than $14 billion was pledged to the GGWI at the 2021 One Planet Summit, yet much of it remains stuck in bureaucratic limbo. Unlocking those funds and ensuring they are channeled to projects on the ground will determine whether the initiative delivers on its promise. Just as crucial is strengthening the Pan African Agency of the Great Green Wall to coordinate the patchwork of governments, NGOs and donors involved, so that projects don’t fall victim to fragmentation or mismanagement.

If that happens, the GGWI could be proof that Africa’s call for investment over aid is more than rhetoric. It would show that large-scale, African-led projects can deliver not only on climate adaptation and livelihoods, but also on peace and stability without deepening dependency or opening the door to new vulnerabilities.

Africa is right to demand investment on its own terms. The Great Green Wall shows that when ambition is matched with governance and genuine local ownership, the shift from aid to investment can move beyond empty pledges to real impact. That is the opportunity Africa has set before the world.

This article draws on the Africa’s Climate Security Risk Pathways Report by adelphi. Figure 1 can be found on Page 5 of the report. For further updates on the Africa Climate Summit 2025, find the joint press statement here.

This article is published by the Clingendael Institute and is written by research assistant Finn van der Straaten.

Photo credits: Hawi Getachew/Unsplash.